Code comes from humans, is written by humans, and solves human problems. That's all there is to it. But behind that, there is a hidden fact that tries to speak to the surface that it means nothing less than understanding humans.

When to be human

Code is read more than written. We read when we want to add new functionalities to the system. We read when it needs to be refactored. We read when we want to improve the performance of the execution. We read when we want to debug the code. So, clarity is of the utmost importance.

A study concluded that meaningful names, consistency, and comments have a strong beneficial influence on improving code readability. On the other side, arithmetic expressions, nested loops, and recursive functions demonstrated a detrimental influence. Another study confirmed that spacing is the second most important factor in code readability.

Meaningful names are essential so that we don't lose track of what's going on when reading, while comments give us the ability to understand the code in a more holistic way. As for spacing, it serves as a visual cue that helps us read the structure of the code, as well as helping us focus on key information.

function p(x) {

return x * 0.453592;

}

let w = p(150);

console.log(w);

See if there's any differences from the above:

function poundsToKilograms(pounds) {

const conversionFactor = 0.453592;

return pounds * conversionFactor;

}

let weightInKg = poundsToKilograms(150);

console.log(`Weight: ${weightInKg} kg`);

Code should be communicative, so that code reviews, pair programming, and systems collaboration can occur. Nowadays, it's hard to find code that can stand alone, it's more easy to find code that's part of something bigger than itself.

Code also needs to show empathy in collaboration. Our teams interact more while writing code than after it goes to production, right? So our communication should be as effective as possible.

function getCompletedTasks(tasks) {

let completedTasks = [];

for (let index = 0; index < tasks.length; index++) {

if (tasks[index].status === "completed") {

completedTasks.push(tasks[index]);

}

}

return completedTasks;

}

let taskList = [

{ title: "Buy groceries", status: "completed" },

{ title: "Wash car", status: "pending" },

{ title: "Pay bills", status: "completed" },

];

const completedTasks = getCompletedTasks(taskList);

console.log("Completed Tasks:", completedTasks);

Compared it to the following:

function getCompletedTasks(tasks) {

return tasks.filter(task => task.status === "completed");

}

let taskList = [...];

const completedTasks = getCompletedTasks(taskList);

console.log("Completed Tasks:", completedTasks);

We agreed that code impacts real people and real businesses, so human-centered thinking is essential. It's by no means that the code should only can be read by us, because we're human too, but it should also be readable by most humans. Code impacts all the humans who collaborated in writing it and it impacts all the humans who make use of it, that's what it means.

Meanwhile, code impacts real business meaning it impacts all the humans involved in passing the baton. Because there's hardly any software that doesn't require maintenance at all. Keeping code relevant is part of the business.

In the previous example, we saw that one-liner is more readable. But that's not always true. Let's look at the following example.

const taskCounts = tasks.reduce((acc, task) => (acc[task.status] = (acc[task.status] || 0) + 1, acc), {});

Now, look at the alternative:

const taskCounts = tasks.reduce((acc, task) => {

acc[task.status] = (acc[task.status] || 0) + 1;

return acc;

}, {});

Well, perhaps it doesn't have to be this way either:

const taskCounts = tasks.reduce((acc, task) => {

if (!acc[task.status]) {

acc[task.status] = 0;

}

acc[task.status]++;

return acc;

}, {});

We may insist, but all our team members can read the first version! Yes, that may be true. However, what if a junior joins the team and everyone is too busy to add non-significant functionality to the code?

Open-source softwares usually have complete technical guidelines on writting code, because the amount of people contributing to the code is huge. Even if it doesn't, our code won't be accepted because it might not be formatted the same way as the rest.

So, once again, think of the human first, as humans.

When to not be human

The code runs well, it meets business needs. However, after going through the stress tests, it feels slow below the tolerance level.

This is when we start to think that the most readable solution isn't the most efficient. See the example below.

function isEven(num) {

return (num & 1) === 0;

}

Instead of this:

function isEven(num) {

return num % 2 === 0;

}

We know, this is rarely useful. But when it comes to developing a game, it can helps a lot. Because we've to make sure the whole process is executed within 1/60th of a second.

Here's another scenario:

const arr = new Array(1_000_000).fill(0);

Then, look at this:

const arr = new Array(1_000_000);

for (let i = 0; i < 1_000_000; i++) {

arr[i] = 0;

}

Or even faster one:

const arr = new Int32Array(1_000_000);

The latter is considered more non-human although still readable as it's not as intuitive and explicit as the others.

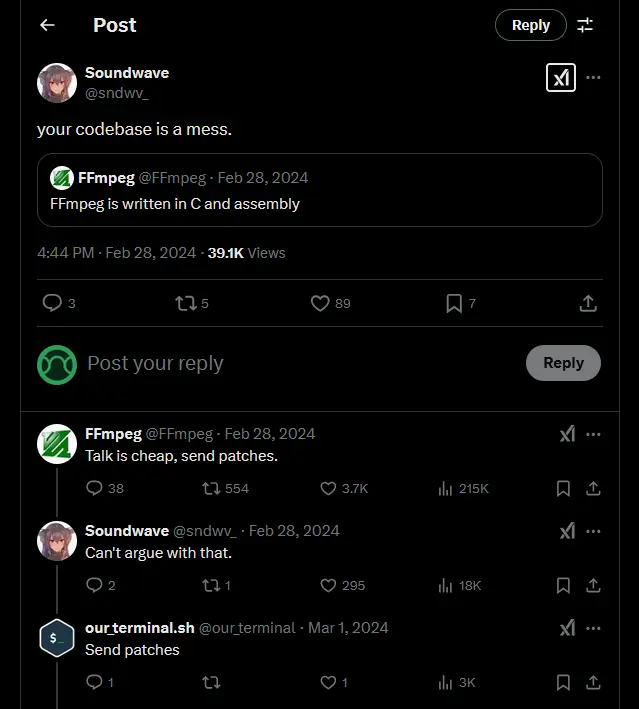

Other times, readable code may not align with our values. For instance when working closely to hardware, readibility takes a backseat to precise control over execution.

As we can see in the above case, readability is not a factor when working with Assembly, or anything that's low-level.